Dev Diary #12: Succession

11:05, 02 Jul 2022

Hello and welcome to the 12th development diary of Grey Eminence!

Today, we’ll be covering the topic of succession. The process of succession determines the future rulers of every country, so it’s a very important mechanic to consider. Every country’s succession can be either dynastic or electoral. The specifics of which characters are eligible to rule and how the top candidate is selected upon the death (or expiration of mandate) of the current ruler are defined by the country’s succession laws, which we’ll explore in a moment.

Dynastic

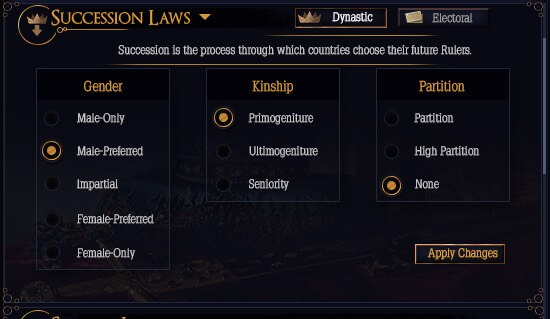

At the start of the game in 1356, the majority of countries on Earth practice some form of dynastic succession. The mechanics of this type of succession are similar to those you’d find in other grand strategy titles. There are three laws which govern how a dynastic succession works: kinship, gender, and partition.

The kinship law determines what kind of biological relationship provides the strongest justification for inheritance. The most common kinship law in use at the start of the game is primogeniture, according to which the eldest child of the current ruler should inherit. A similar, yet less common kinship law is ultimogeniture, which dictates that the youngest child should inherit. The final kinship law is seniority, by which older members of the ruling dynasty are valued more highly than younger ones.

Usually, succession is restricted to characters of a certain gender. Most religions restrict which gender succession laws are available, with the vast majority of countries in the game starting off with either the male-only or male-preference law, that respectively either outright disqualifies or heavily penalizes female characters as long as there are eligible male heirs. Note that even if a character is nominally disqualified from succession, they may still try to steal the crown anyway via a faction (which will also change the gender succession law if successful).

The partition law is the one with the most potential for headaches, as it dictates whether secondary heirs receive land of their own. By 1356, most countries had transitioned away from partition (due to its tendency to weaken the realm), yet there are still some countries that practice it. Partition can only be enabled for countries with Duchy rank or higher. Whenever succession happens in such a country, new county-level vassal countries will be created for each eligible heir out of the non-capital provinces of the country. In essence, this ensures that the country’s royal domain will not extend beyond its capital province until partition is repealed. In rare cases, when a country with partition owns enough territory (or controls enough people) to create an equal-rank title, new independent countries may split off.

Male-preference, partition-less primogeniture is by far the most common set of succession laws in Europe in 1356. Due to its permission of female heirs, it tends to lead to personal unions over time, a phenomenon that’s relatively rare outside Europe.

Electoral

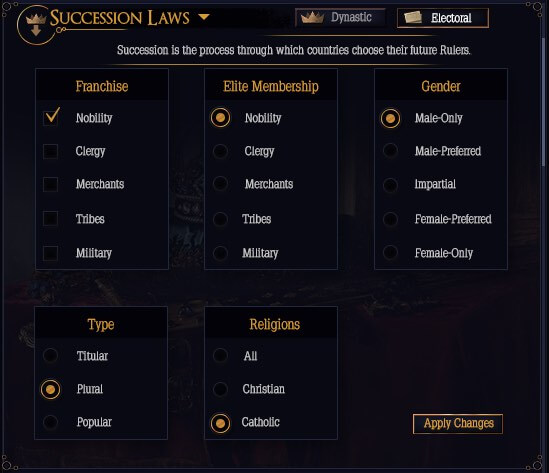

Electoral successions are our catch-all category for all successions that don’t follow the aforementioned dynastic paradigm. The scale and scope of elections varied significantly between 1356 and 1956, but we’ve done our best to design the system to be as versatile and as encompassing as possible. Electoral successions are governed by three main laws: type, franchise, and candidacy.

An election’s type determines the overall structure of the election. The first electoral type we’ll cover is titular. In titular elections, votes are allocated to the rulers of specific countries (usually, but not always, vassals). The classic example of a titular election is the succession of the Holy Roman Empire, where votes are assigned to whichever characters rule Brandenburg, Saxony, Bohemia, the Palatinate, Trier, Cologne, and Mainz. In the case of a single character controlling multiple electoral titles, they get to exercise their collective voting power (though other electors will likely take offense at such an injustice). The ruler, of course, can always retract or bestow electoral privileges on other vassals, but that will likely draw the ire of existing electors.

The second electoral type is plural, which grants electoral privileges to all characters within the parent country that belong to one (or more) elites + all vassals with a matching government form. For example, an aristocratic monarchy might empower the nobility and the clergy to decide on its future rulers, which will grant voting rights to all noble/clergy characters within the country’s domain (but not within the domains of its vassals). If some of the country’s vassals happen to have a religious or dynastic source of legitimacy, they too will be able to participate in the election. Importantly, an oligarchic country with plural elections must allow the ruling elite to vote, so the nobility in an aristocratic monarchy will always have a say in plural elections.

The final electoral type is popular. This type of succession works quite differently from the previous two, since it’s not determined by characters. Depending on the franchise law (which we’ll cover in a second), certain parts of the country’s population will get to elect the country’s rulers - and their representatives in parliament, if such an institution exists in the country. Popular elections are closely tied to political parties and general elections, so we’ll go in more detail on how this all plays out in another dev diary.

The franchise law builds upon the election’s type to define who exactly gets to participate in the election. In the case of titular elections, the law opens up a dedicated UI, where you can retract electoral privileges from existing electors or grant these privileges to other vassals. For plural elections, the franchise law allows you to select which elites are endowed with electoral privileges. A plural election will always have at least one voting elite (in the case of oligarchies, the ruling elite), but other elites can be empowered as well to create a more diverse and balanced electorate, which also gives you one more avenue through which to play the elites against one another. Franchise laws in popular elections determine the scope of suffrage: this can range from allowing only specific cultures or denominations to vote to extending suffrage to all adults in the country. But again, more on popular elections in their dedicated dev diary.

The candidacy laws are a set of laws that restrict the eligibility of characters to stand for election. Currently, the set is comprised of gender, culture, religion, and elite belonging laws (e.g. only nobles, which includes both elites and rulers of dynastic countries), but this isn’t final and may change in the future.

One thing we’d like to emphasize is that these are the default set of electoral & dynastic succession laws. While we’re avoiding the inclusion of country-specific (or religion/culture-specific) succession laws initially, we hope to eventually be able to add more detailed representations of the unique types of successions that occurred during the span of Grey Eminence. We’re not making any guarantees here, but we’ve purposefully designed the succession system to be capable of handling such unique cases.

The default electoral election in 1356 empowers the nobles of the realm (both elites & dynastic vassals) to elect their future liege.

Interregnums & Regencies

Succession wasn’t always a straightforward affair. Whenever there are multiple competing heirs with similarly strong claims to the throne, an interregnum might happen. This special circumstance lasts from the death of the previous ruler until the undisputed ascension of the victorious heir. Interregnums aren’t necessarily bound to escalate into civil war, but even having parts of the realm not recognize the new ruler can have disastrous consequences. How exactly interregnums play out - and how vassals & foreign countries can intervene, which is the juicy part - will be the subject of a separate dev diary, so stay tuned!

Similarly, regencies are a special circumstance that occurs whenever the ruler of a country is a child. Regencies always feature a regent, a powerful character who exerts significant influence over the country while they (supposedly) care for the young ruler. Regencies are one of the situations where a country might backslide on its progress, especially when the regent is a member of the elites. As with interregnums, regencies will be getting their own dev diary later down the line, during which we’ll go into full detail on how they play out and how you can manage them.

Moddability

As we mentioned before, we’ve intentionally designed the succession system to be as open-ended as possible, so that custom succession types are easy to add. Specifically, adding succession types that utilize the data we’re already using for the existing ones (e.g. specific countries, specific elites, specific cultures or religions) can be done via the world editor. In order to utilize different data you’ll need to perform a bit of C# wizardry, but nothing too complex. Succession is one of the more moddable systems, since we want to allow modders to create as many different, unique, and niche succession types as possible for mods (both historical and fantasy).

That’s all this time around! We’re taking a short summer hiatus from publishing dev diaries (though behind the scenes we’re keeping the programming elves locked in the mines), so we won’t be releasing the next one until August 6. We hope you have a wonderful start to the summer and - as always - don’t forget to join our Discord and Subreddit, and to follow us on YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter. Thanks for reading!

Back

Back