Dev Diary #5: Religion

13:32, 26 Mar 2022

Hello everyone and welcome to the 5th development diary of Grey Eminence!

In today’s edition, we’ll explore the various mechanics around religion. Prior to the emergence of popular nationalism, faith was the binding force for civilizations across the globe. As such, religion interacts with many other systems in the game and will be something you’ll definitely want to keep a close eye on.

Let’s start by defining what a religion is. In Grey Eminence, religions are not monolithic; instead, they are a collection of individual denominations with shared common beliefs. For example, Christianity is a religion with a lot of denominations, and while all Christians believe in the Abrahamic God, there’s very little agreement on the finer details.

The majority of religious game mechanics are expressed at the denomination level. Each denomination is defined by its combination of doctrines, stances, and idiosyncrasies. Notably, the combination doesn’t have to be unique, though you’ll see why that matters a bit farther down.

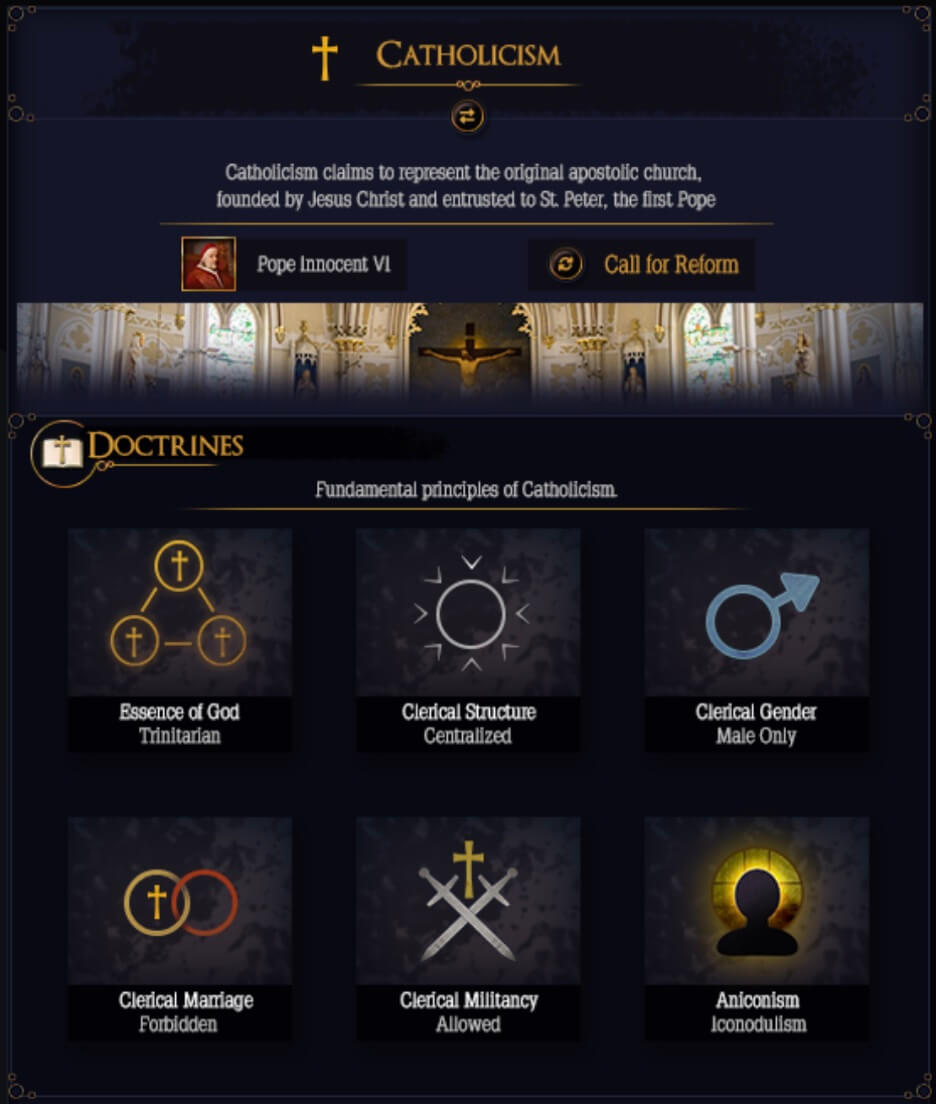

Doctrines

Each denomination has a set of doctrines, which define its overall structure and high-level mechanics. You can think of doctrines as the building blocks of a given denomination: all religions have access to the same types of doctrines, though most have restrictions on which specific doctrines they can select.

Doctrines control everything from how the denomination’s clergy is organized, its theological foundations, which genders are allowed to join the clergy, whether the clergy can marry, and more. We won’t go through all doctrines now, just the most important one, namely clerical structure.

Clerical structure tells us how the clergy of a given denomination is organized (if at all). This doctrine has knock-on effects on most other aspects of the denomination, so it’s arguably the foundation of every denomination. There are four options here: unorganized, autonomous, semi-autonomous, centralized.

When a denomination is unorganized, it has no formal clergy. This doctrine is most common among folk religions, though it can appear elsewhere too. Countries that follow unorganized denominations won’t have a clergy elite, which can have significant implications for their power balance. Without the clergy, the other elites have one less counterweight to worry about in their eternal quest for power. There are less obvious impacts too: for example, education becomes much more difficult in pre-industrial societies without a clergy elite. We’ll talk more about reformation later, but disorganized denominations are the easiest ones to reform, since there isn’t any organized religious body that can rise up in opposition.

Autonomous denominations have a clergy, but it is purely local with no higher-tier authority. This usually (but not always) results in a weak and/or corrupt clergy, depending on the country’s investiture law. Without any real organized governance, an autonomous clergy is at the mercy of the player and other elites, for better or worse. Examples of autonomous denominations are Shinto and the various flavors of Buddhism.

Semi-autonomous denominations have a clergy that is organized no higher than the country level. The prime example of such a denomination is Eastern Orthodox Christianity, where each country’s church can potentially have its own leader and can consider itself independent (autocephalous). How such country-level leaders are elected is determined by a separate doctrine that we won’t cover today. In any case, semi-autonomous clergy elites have the potential for significant power accumulation, though once their power is broken, they won’t be able to rely on any external authority to get it back.

Centralized denominations have a clergy that is organized on the international level with a fully-fledged head of faith. These denominations have the greatest ability to exert power and accumulate resources. They also have the widest variety of potential doctrines that govern their structure and abilities, like extracting cross-border tithes or hosting globe-spanning conclaves. Catholicism is the best example of just how far a centralized denomination can go: while in 1356 the Papacy’s temporal domain is restricted to Central Italy, the Pope wields political and economic influence across Europe.

The religious UI shows the key features of the selected denomination, in this case Catholicism. Most doctrines are self-explanatory, while the theological ones impact relations with other denominations and allow/prohibit certain stances and idiosyncrasies. As usual, everything is WIP.

Stances

Historically, one of the purposes of religion was to tell you how to live your life. This is where stances come in. Each denomination can have an official stance on any number of social, political, and economic issues. Crucially, individual countries can override them with their own local stances, which reflect traditional (usually cultural) practices that are at odds with their denomination’s formal teachings.

Such conflicts can be resolved in many ways. If the denomination has a head of faith, they might coerce errant countries through social, political or even military means. Calls to adherence can also emerge spontaneously from the local clergy. Conversely, stance conflicts can grow into outright heretical schisms, though more on that later.

To give you an example that has an interesting impact on gameplay, let’s look at the stance on divorce. The options here are: forbidden, spiritually-approved, and allowed.

When a denomination totally forbids divorce, a marriage can only be ended through annulment. This procedure is different from divorce in that it retroactively deems a marriage (and all its products!) to be invalid.

For a monarchy, annulment can have disastrous consequences. Let’s say your ruler decides to annul his marriage and to remarry someone else (God forbid they also have children). Even if the head of faith agrees to it - which they might not, leading to a host of other problems - you’ve suddenly got a succession crisis on your hands. Any children from the annulled marriage would be considered illegitimate, and depending on their personality and resources, they might not take that very well.

Spiritually-approved divorce places the process under the control of the clergy (specifically the head of faith for centralized denominations). Depending on their power, the clergy might extract a harsh cost in “donations” or favors for granting someone the privilege of divorce.

When divorce is allowed it becomes a lay affair. This doesn’t mean that it won’t have consequences: the family of the divorcee may well have something to say even if the process is fully legal.

Stances most often impact character relations. As you can see above, being Catholic during the Middle Ages wasn’t particularly fun.

Idiosyncrasies

So far, we’ve covered the religious mechanics that are shared by all denominations. In contrast, idiosyncrasies are unique mechanics that are usually restricted to certain religions or theological doctrines. They not only give each denomination its own flavor, but also make its gameplay distinct.

We’ve got a lot more idiosyncrasies planned than doctrines or stances; examples include baptism, legalism, human sacrifice, and pacifism. All these idiosyncrasies add unique mechanics to various aspects of the game. While they aren’t as earth-shattering as doctrines or stances, they’re nevertheless tangible; at minimum, an idiosyncrasy will unlock character relations, events, or population behaviors.

The example idiosyncrasy we’ll look at is monasticism, which by default is present in most Christian and some Buddhist/Hindu denominations. Countries (or elites/populations) that follow monastic denominations can construct monastery buildings in tiles, which employ monks/nuns. These spiritual sanctuaries can significantly increase the literacy rate of their communities and can accelerate the emergence of certain technologies. Additionally, they provide a convenient location to exile your unneeded heirs or defeated political opponents.

The rites and sacraments of Catholicism had a significant impact on the lives of people and their relations. They unlock specific mechanics that usually serve to empower the clergy.

Reformation, Heresy & Schism

We’ve mentioned previously that religions and cultures in Grey Eminence aren’t static. Now we’ll give you a bit of insight into how denominations can change over time, although you’ll learn the full details in a separate dev diary later down the line.

Reformation and heresy are the two main ways a denomination can change, and they’re really two sides of the same coin. Both processes aim to change aspect(s) of a certain denomination: this can be any combination of doctrines, stances, and idiosyncrasies. Their outcomes, however, are radically different. In the case of reformation, the denomination remains whole, albeit modified. With heresy, an entirely new denomination emerges to challenge the previous order.

There are two ways in which reformation or heresy can start: top-down or bottom-up. Top-down calls for reform usually originate from people in positions of power, either rulers, heads of faith, or members of the elite, though you yourself can call for it in your ruler’s name. For example, a catholic king might be so unhappy with the Pope for rejecting his annulment request that he tries to start his own denomination where divorce is allowed (looking at you, Henry VIII). On the flip side, when multiple rulers or high-level clergy members campaign for the same cause, honest reformation is possible. For denominations with non-centralized structures, the same conflicts happen on a smaller scale within the country.

Change can also arise from the population, represented by less-powerful characters. As we discussed before, conflicts between faith and culture can escalate either way: the culture might abandon its sinful ways or a full-blown heresy could emerge. In other cases, charismatic (and usually lowborn) preachers may appear, whose teachings you can either encourage or suppress. Heresy is oftentimes disruptive, yet it can also bring opportunity.

Crucially, religious fragmentation need not happen for purely theological reasons. Politics can inspire ambitious characters to branch out without any meaningful differences in doctrines, stances, or idiosyncrasies. This creates a schism and is how you can get antipopes. Unlike heresies, schisms are reversible, though we won’t go into detail now.

Moddability

As with our other gameplay systems, religions and denominations are fully moddable. This includes not just content-level changes, like adding/removing/modifying doctrines, stances, and idiosyncrasies, but also systematic changes. Under the hood, all the components of a denomination function the same way: they either allow or prohibit a certain mechanic. Thus, you can rewire a specific doctrine to unlock, for example, access to new types of units or government forms. With some amount of coding effort, you can add your own custom mechanics and link them to certain denominations, which could be the basis for a system of magic in a fantasy mod. There are a lot of possibilities here and we can’t wait to see what you guys come up with!

Anyway, that’s all we’ve got for you this time around. Stay tuned for the next dev diary on April 9, and until then make sure you’ve joined our Discord and Subreddit, and follow us on YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter. Thanks for reading and take care!

Back

Back